Learn About American Kestrel Falcon

The American Kestrel (Falco sparverius) was originally known in North America as the “Sparrow Hawk”. This name is misleading because it implies a connection with the Eurasian Sparrowhawk (Accipiter nisus), which is unrelated.

The American Kestrel is the smallest falcon in North America. The female ranges in length from 9-11 in (23-28 cm) with a wingspan of 21-24 in (53-61 cm) and weighs an average of 4.2 oz (120 g). The length of the male varies between 8-10 in (20-25 cm) with a wingspan ranging from 20-22 in (51-56 cm) and weighing an average of 3.9 oz (111 g).

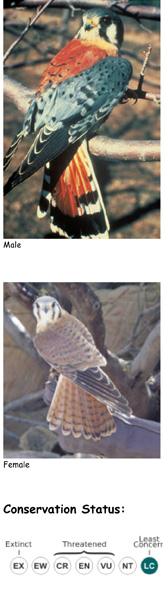

Oppositely to other raptors, there is a definite sexual dimorphism with this species, meaning that the coloration of the feathers greatly varies between the sexes. Males have blue-grey feathers on their wings, while the undersides are white with black barring. The back is rufous in coloration, with barring on the lower half. The belly and flanks are white with black spotting. The tail is also rufous.

The back of the female American Kestrel is rufous with dark brown barring. The wings exhibit similar coloration and patterning to the back. The undersides of the females are white with rufous streaking. The tail of the female is noticeably different from the male, being rufous in color with numerous narrow dark brown or black bars.

In both sexes, the head is white with a bluish-grey top. There are also two narrow, vertical black facial markings on each side of the head; one below the eyes and one on the sides. Two black spots (ocelli) can be found behind their head and resembles eyes.

American Kestrels are widely distributed across the Americas. Their breeding range extends from central and western Alaska across northern Canada to Nova Scotia, and south throughout North America, into central Mexico, the Baja, and the Caribbean. They are local breeders in Central America and are widely distributed throughout South America.

Most of the birds breeding in Canada and the northern United States migrate south in the winter.

American Kestrels are found in a variety of habitats including parks, suburbs, open fields, forests and prairies.

The American Kestrel is the only North American falcon to habitually hover with rapid wing beats, keeping its head motionless while scanning the ground for prey.

This falcon species is not long-lived. The oldest banded wild bird was 11 years and seven months old while a captive lived 17 years. Major causes of death include collision with traffic, illegal shooting, and predation. Because of its small size, the American Kestrel is a common prey item of other raptors.

In summer, kestrels feed largely on grasshoppers, dragonflies, lizards, mice, and voles. They will also eat other small birds.

American Kestrels form pairs in which the bond is strong, tending toward permanence. Returning migrants commonly re-establish territories held the previous year. Nesting occurs from late spring to late summer in North America, with incubation underway by the end of May.

A cavity nester, American Kestrels will use holes in trees, rock cavities and crevices in cliffs, artificial nest boxes, or small spaces in buildings. The number of suitable breeding cavities limits this species’ breeding density. The American Kestrel has adapted well to nest boxes.

Both sexes take turns incubating their eggs, a very rare situation among North American birds of prey where the female usually incubates exclusively.

There are in average four to six eggs per clutch and they hatch 29 to 31 days after being laid.

As this bird occurs over a wide range and is not generally rare. The American Kestrel’s North American population has been estimated at 1.2 million pairs. It is possible that the clearing of parts of North America for agriculture in the last two hundred years has caused the American Kestrel population to increase.

Threats to the species as a whole include loss of nest sites, pesticide poisoning (dieldrin and DDT, among others), and death through collisions with vehicles as well as shooting.

Scientific Classification:

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Aves

- Order: Falconiformes

- Family: Falconidae

- Genus: Falco

- Species: F. sparverius

References: * BirdLife International (BLI) (2008). Falco sparverius. 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN 2008. Retrieved on 06 November 2008. * Brodkorb, Pierce (1964): Catalogue of Fossil Birds: Part 2 (Anseriformes through Galliformes). Bulletin of the Florida State Museum 8(3): 195-335. * Cisneros-Heredia, Diego F. (2006): Notes on breeding, behaviour and distribution of some birds in Ecuador. Bull. B.O.C. 126(2): 153-164. * Ehrlich, Paul Ralph; Dobkin, D. & Wheye, D. (1988): The Birder’s Handbook: A Field Guide to the Natural History of North American Birds. Simon & Schuster Inc., New York. * Faria, Christiana M.A.; Rodrigues, Marcos; do Amaral, Frederico Q.; Módena, Érica & Fernandes, Alexandre M. (2006): Aves de um fragmento de Mata Atlântica no alto Rio Doce, Minas Gerais: colonização e extinção [The birds of an Atlantic Forest fragment at upper Rio Doce valley, Minas Gerais, southeastern Brazil: colonization and extinction]. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 23(4): 1217-1230 * Griffiths, Carole S. (1999): Phylogeny of the Falconidae inferred from molecular and morphological data. Auk 116(1): 116–130. * Griffiths, Carole S.; Barrowclough, George F.; Groth, Jeff G. & Mertz, Lisa (2004): Phylogeny of the Falconidae (Aves): a comparison of the efficacy of morphological, mitochondrial, and nuclear data. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 32(1): 101–109. * Groombridge, Jim J.; Jones, Carl G.; Bayes, Michelle K.; van Zyl, Anthony J.; Carrillo, José; Nichols, Richard A. & Bruford, Michael W. (2002): A molecular phylogeny of African kestrels with reference to divergence across the Indian Ocean. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 25(2): 267–277. * Henninger, W.F. (1906): A preliminary list of the birds of Seneca County, Ohio. Wilson Bull. 18(2): 47-60. * Ragusa-Netto, J. (2000): Raptors and “campo-cerrado” bird mixed flock led by Cypsnagra hirundinacea (Emberizidae: Thraupinae). Revista Brasileira de Biologia 60(3): 461-467 * Terres, John K. & National Audubon Society (NAS) (1991): The Audubon Society Encyclopedia of North American Birds. Wings Books, New York. Reprint of 1980 edition. * US Code of Federal Regulations (US CFR) (2005): Title 50; Chapter 1; Part 21: Migratory Bird Permits. Version of October 1, 2005. * Varland, Daniel E. & Loughin, Thomas (1992): Social Hunting in Broods of Two and Five American Kestrels after Fledging. Journal of Raptor Research 26(2): 74-80 * Wink, Michael & Sauer-Gürth, Hedi (2000): Advances in the molecular systematics of African raptors. In: Chancellor, R.D. & Meyburg, B.-U. (eds): Raptors at Risk: 135-147. WWGBP/Hancock House, Berlin/Blaine. * Wink, Michael; Seibold, I.; Lotfikhah, F. & Bednarek, W. (1998): Molecular systematics of holarctic raptors (Order Falconiformes). In: Chancellor, R.D., Meyburg, B.-U. & Ferrero, J.J. (editors): Holarctic Birds of Prey: 29-48.