Learn About Merlin Falcon

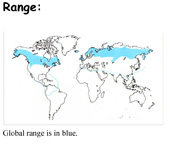

in northern North America, Europe and Asia. This bird of prey is 24-33 cm (9.5-13 in) long with a 53-69 cm (21-27 in) wingspan. Males average at about 165 g (5.8 oz) and females are typically about 230 g (8 oz). Compared to other small falcons, they are more robust and heavily built. The male Merlin has a blue-grey back and orange-tinted underparts. The female and immature are dark brown above and whitish spotted with brown below.

Merlins breed in open country such as moorland, taiga or willow or birch scrub. Like the larger Peregrine Falcon, it is migratory, wintering in more temperate regions. Northern European birds move to southern Europe and North Africa, and North American populations to the southern USA and northern South America. In winter, the Merlin may be found in almost any open country, from coasts to prairies to desert scrub. In the mildest parts of its breeding range, such as Great Britain, it will desert higher ground and move to coasts and lowland.

Most of their preys consist of small birds like sparrows, pipits and sandpipers.

Most Merlins will use abandoned corvid or hawk nests which are in conifer or mixed tree stands. They will also set up a nest on cliff-faces and on the ground.

Usually four rusty brown eggs are laid. The incubation period is 28 to 32 days. The female does almost all of the incubating, while the male hunts and feeds both her and their young. Hatchlings are brooded for about 7 days. The fledging stage is reached at about 29 days.

Corvids are the primary threat to eggs and nestlings. Adult Merlins may be preyed on by larger raptors, especially Peregrine Falcons, Great Horned Owls and larger hawks (like Goshawks), but most other birds avoid Merlins due to their aggressiveness.

Scientific Classification:

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Aves

- Order: Falconiformes

- Family: Falconidae

- Genus: Falco

- Species: F. columbarius

References: * Feduccia, J. Alan (1970): Some birds of prey from the Upper Pliocene of Kansas. Auk 87(4): 795-797. * Griffiths, Carole S. (1999): Phylogeny of the Falconidae inferred from molecular and morphological data. Auk 116(1): 116–130. * Groombridge, Jim J.; Jones, Carl G.; Bayes, Michelle K.; van Zyl, Anthony J.; Carrillo, José; Nichols, Richard A. & Bruford, Michael W. (2002): A molecular phylogeny of African kestrels with reference to divergence across the Indian Ocean. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 25(2): 267–277. * Helbig, A.J.; Seibold, I.; Bednarek, W.; Brüning, H.; Gaucher, P.; Ristow, D.; Scharlau, W.; Schmidl, D. & Wink, Michael (1994): Phylogenetic relationships among falcon species (genus Falco) according to DNA sequence variation of the cytochrome b gene. In: Meyburg, B.-U. & Chancellor, R.D. (eds.): Raptor conservation today: 593-599. * Henninger, W.F. (1906): A preliminary list of the birds of Seneca County, Ohio. Wilson Bull. 18(2): 47-60. * Martin, R.A.; Honey, J.G. & Pelaez-Campomanes, P. (2000): The Meade Basin Rodent Project; a progress report. Kansas Geologial Survey Open-file Report 2000-61. Paludicola 3(1): 1-32. * Wink, Michael; Seibold, I.; Lotfikhah, F. & Bednarek, W. (1998): Molecular systematics of holarctic raptors (Order Falconiformes). In: Chancellor, R.D., Meyburg, B.-U. & Ferrero, J.J. (eds.): Holarctic Birds of Prey: 29-48. Adenex & WWGBP.